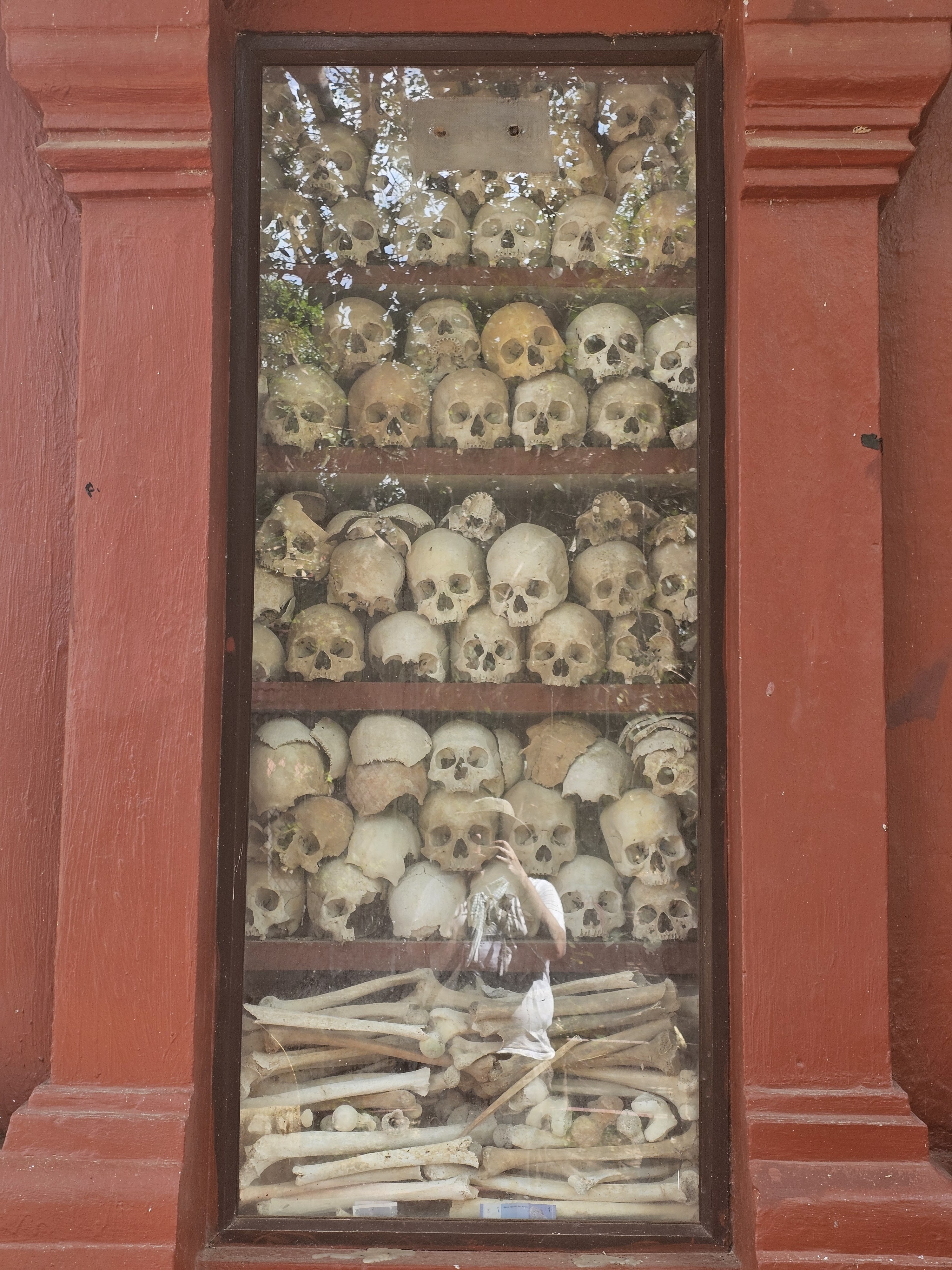

The pagoda shrine to the Killing Fields of Siem Reap, housed on the grounds of Wat Thmey. The pagoda emulates the pagoda at Choeung Ek, though on a much smaller scale.

For some, the country of Cambodia invokes images of a serene idyllic country side, with ancient temples surrounded by jungles and golden rice paddy ripe for the harvest. For others, with longer memories or even personal experiences, there is a darker memory hidden in the fields, forced labor, starvation, persecution, and death. I had first learned of Cambodia from an old 1982 issue of the National Geographic magazine, with sketches of the temples and ruins, but mixed in with these images were soldiers, grim faced civilians, and things my young mind didn’t quite comprehend. I held onto this issue, often returning to these images and after watching the documentary Year Zero by John Pilger in high school. The dualism of idyllic countryside and vestiges of a war-torn nation leaves many who venture there wondering how this came to be.

Cambodia is one of the most memorable countries I have ever visited. It is at times mesmerizing and at other times traumatizing, my trips often weaving the historic temples and the horrors of the Khmer Rouge. Yet I must always remind myself, no country should be seen through the lens of ancient temples or war. It is also the people, and that is perhaps why the period under Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge seems to have us all collectively captivated on the horrors of the period. I often see the question posed, how could a people such as the Khmer ever have been so brutal to their fellow countrymen? And yet, I have never had this question answered to my satisfaction. I dare not even ask, as I only seem to sink deeper into the rabbit hole. There is no perfect answer to this question, perhaps there was never a reason.

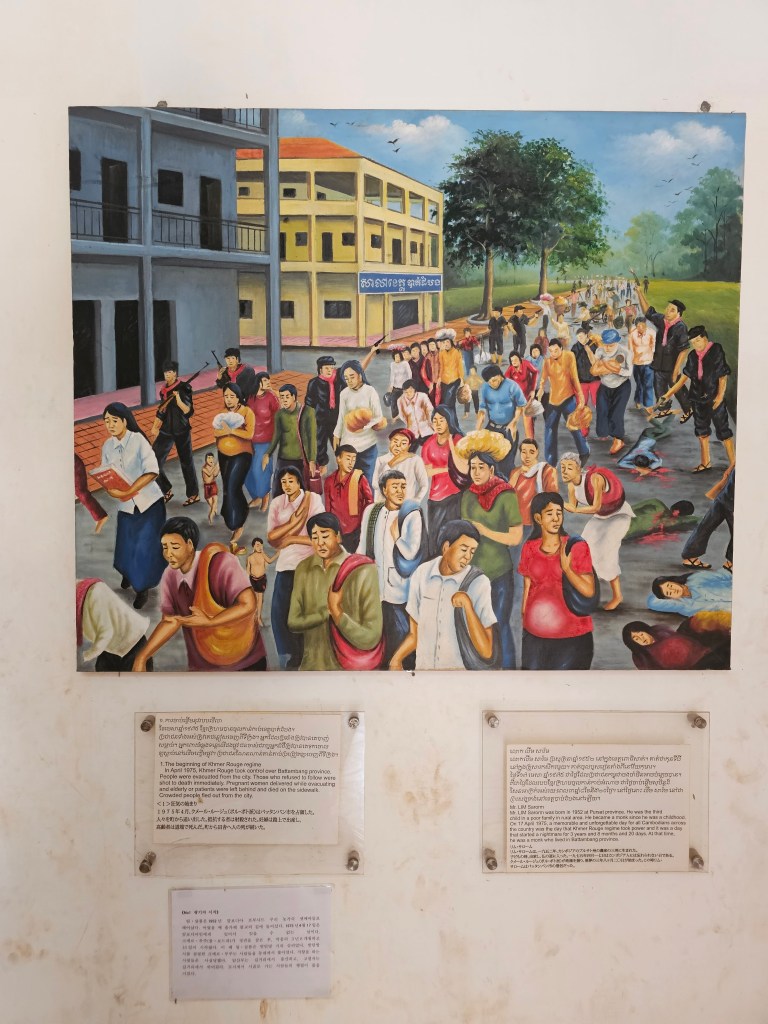

The tale for Siem Reap under the Khmer Rouge plays much as it does with the rest of the nation. As with the capital, Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge ordered the population from the cities to evacuate and disperse into the countryside. Many of the abandoned schools and monasteries across the war-torn nation would be used as detention and torture centers, as well as mass murder sites, the killing fields. Siem Reap, then a much smaller but still important city and gateway to the ancient ruins of Angkor was not spared. The ruins of Angkor Wat were under the control of the Khmer Rouge since 1972, but Siem Reap would remain under government control until the city fell on April 17th, the same day as the fall of Phnom Penh. With the city evacuated, the site of present day Wat Tepothivong was selected as the Khmer Rouge’s detention center of Siem Reap.

First built as a hospital for Chinese engineers building the Siem Reap Airfield, it has undergone several changes. After the end of the Sangkum Reastr Niyum era, the hospital was turned to a military outpost during the Khmer Republic. Later, it would come to be called ‘Thom Prison’ during the Khmer Rouge Democratic Kampuchea era.

The site chosen by the Khmer Rouge was once a hospital built in the era of King turned Prince Sihanouk, during the Sangkum Reastr Niyum era (c. 1955-1970). During the Lon Nol regime of the Republic of Cambodia (c. 1970-1975), it became a military outpost, and was on the front lines defending the town of Siem Reap after Khmer Rouge forces overran the ancient temples of the Khmer Empire. With the fall of the Lon Nol regime, the Khmer Rouge turned the site into a detention center, known as Kuk Thom, or Big Prison, where prisoners from the three provinces of Battambang, Preah Vihear, and Siem Reap would be detained, interrogated-tortured, and executed. The prisoners were brought to the site by covered truck, where they would be held and processed in separate buildings. Outside of the building, many mass graves were dug, and the remains would be discovered around the compound after the Vietnamese drove the Khmer Rouge out of Siem Reap in 1979. Very few would survive a trip to Kuk Thom, one such survivor only managed to survive his detention because his mechanic skills were needed by the regime. His story is briefly described in paintings inside the Killing Fields Museum.

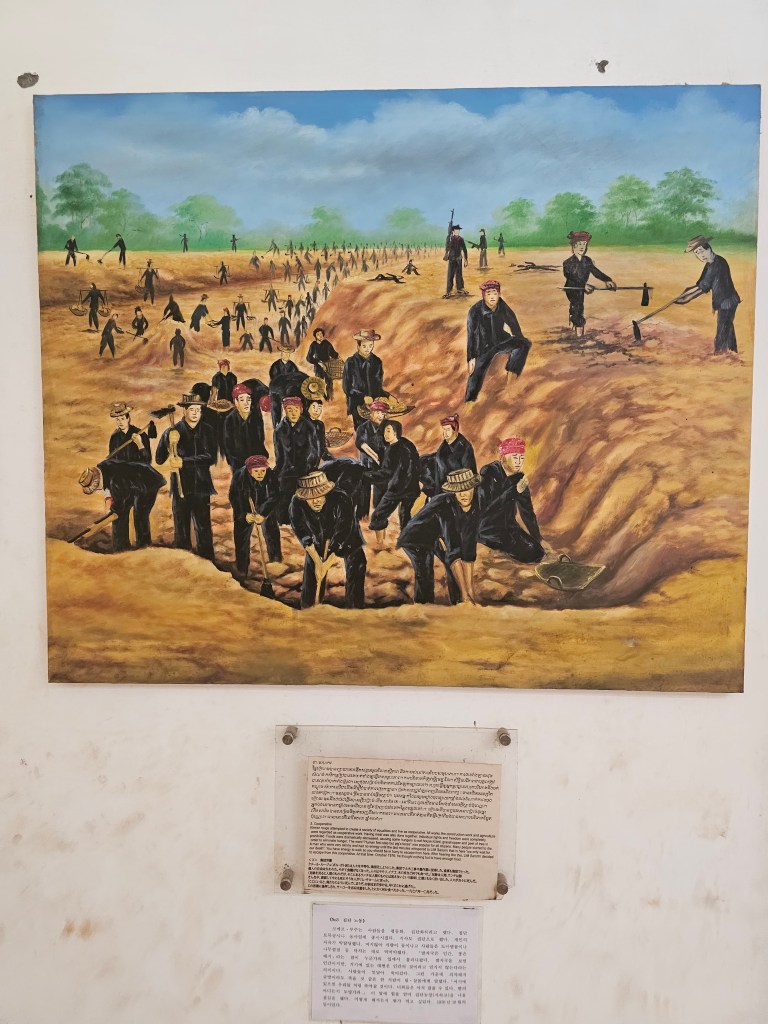

With the Khmer Rouge take over of the country, city dwellers were forced into the country side, where they were put into forced labor across the country digging dikes and reservoirs, often with poor planning and engineering, which resulted in many being washed out. Famines were mostly caused by poor planning and the distribution of the crops out of the areas where they were needed.

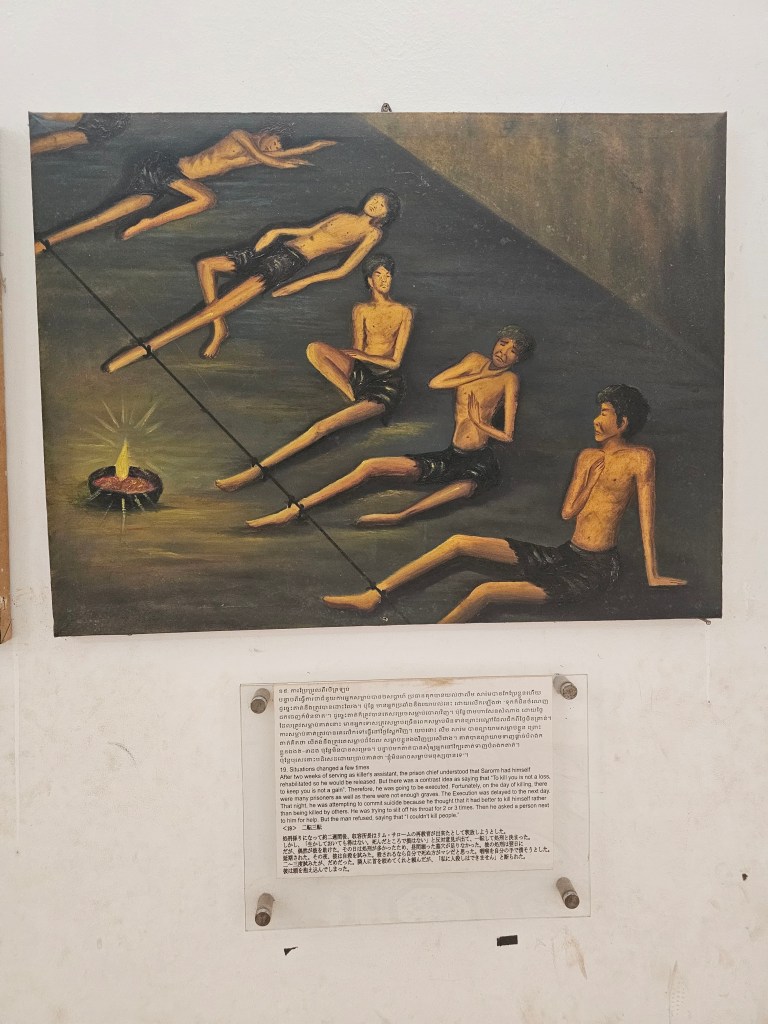

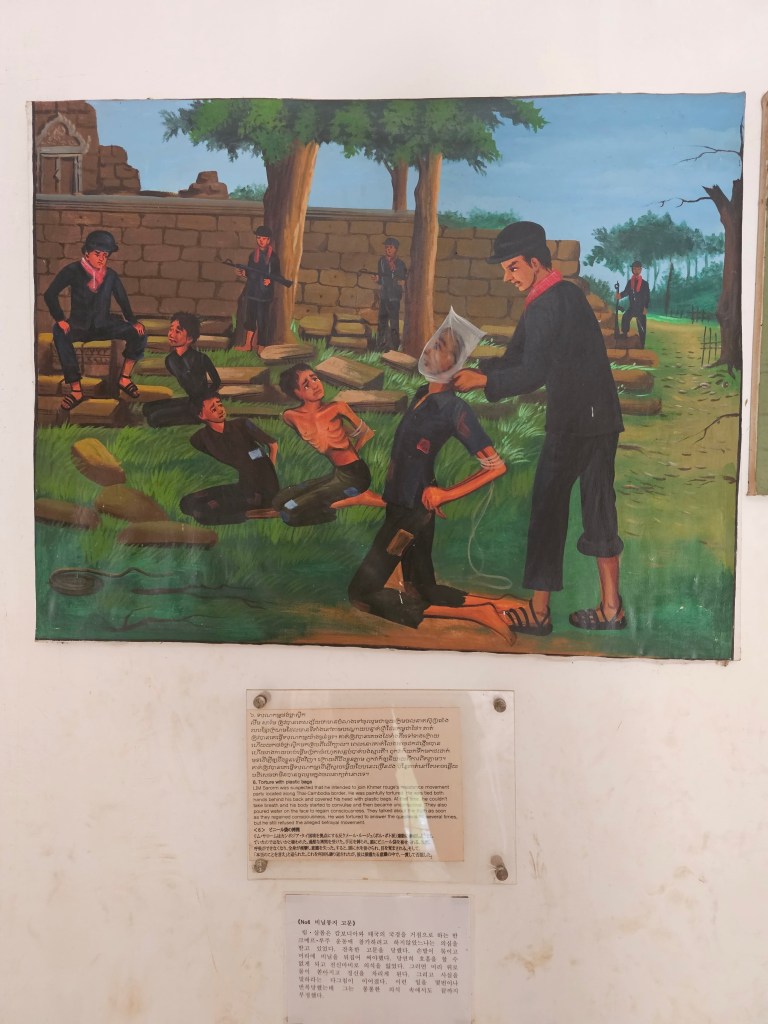

There are two survivor accounts from the Siem Reap area which the Killing Fields museum preserves their narratives. Lim Sarorn, a former monk who was ordered to leave the monk-hood by the Khmer Rouge. He attempted escape due to the forced labor and lack of food. Unfortunately he was captured and sent to a detention center which was a former temple outside of the city. He was accused of attempting to join the resistance along the Thai border, a fiction that the Khmer Rouge created to entice attempts of escape. Lim would eventually be transferred to Kuk Thom in Siem Reap to be executed. However fate intervened and he was made an attendant to the prison commander. In this role he would bear witness to all the atrocities carried out in the name of Angkar (the organization).

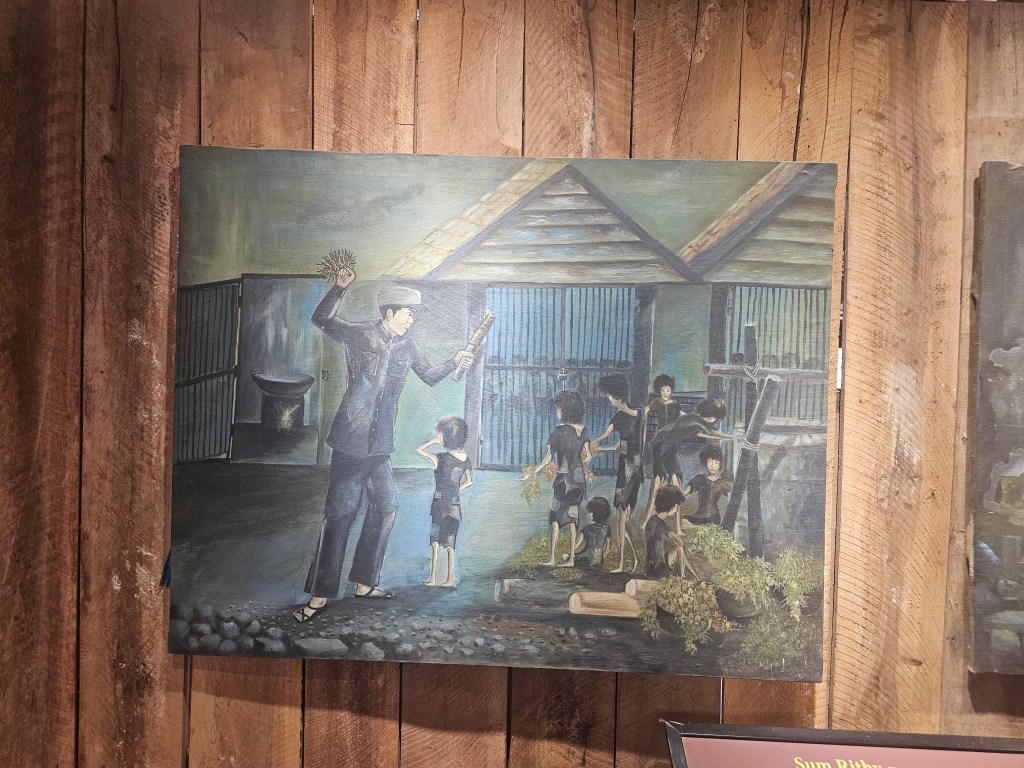

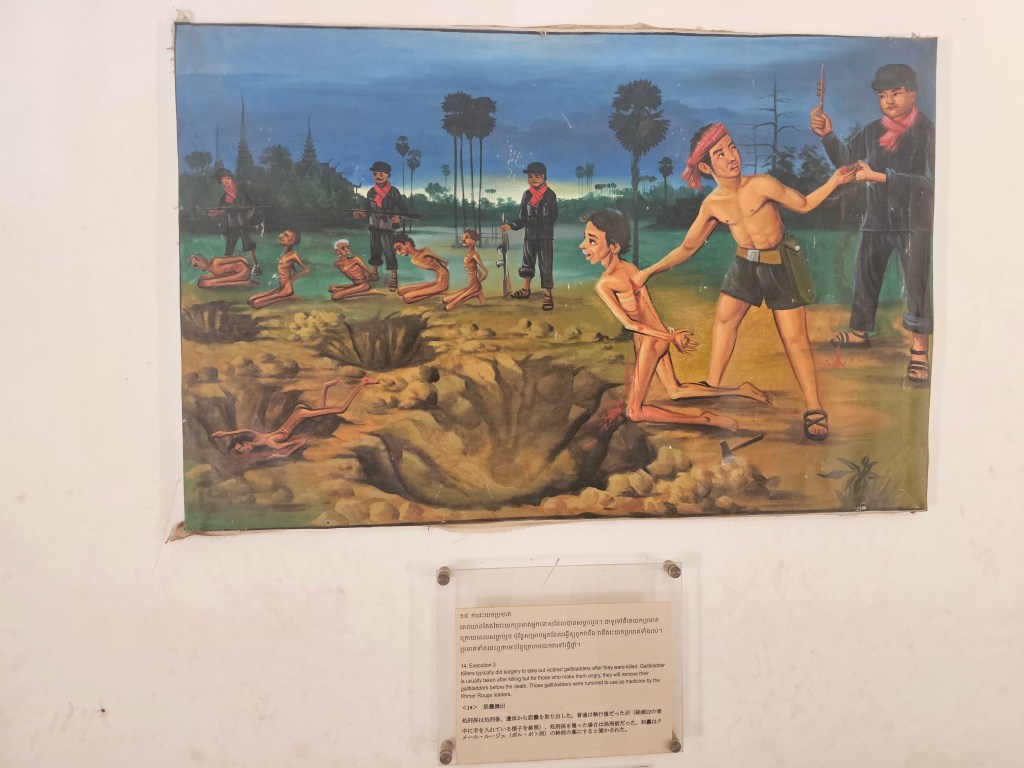

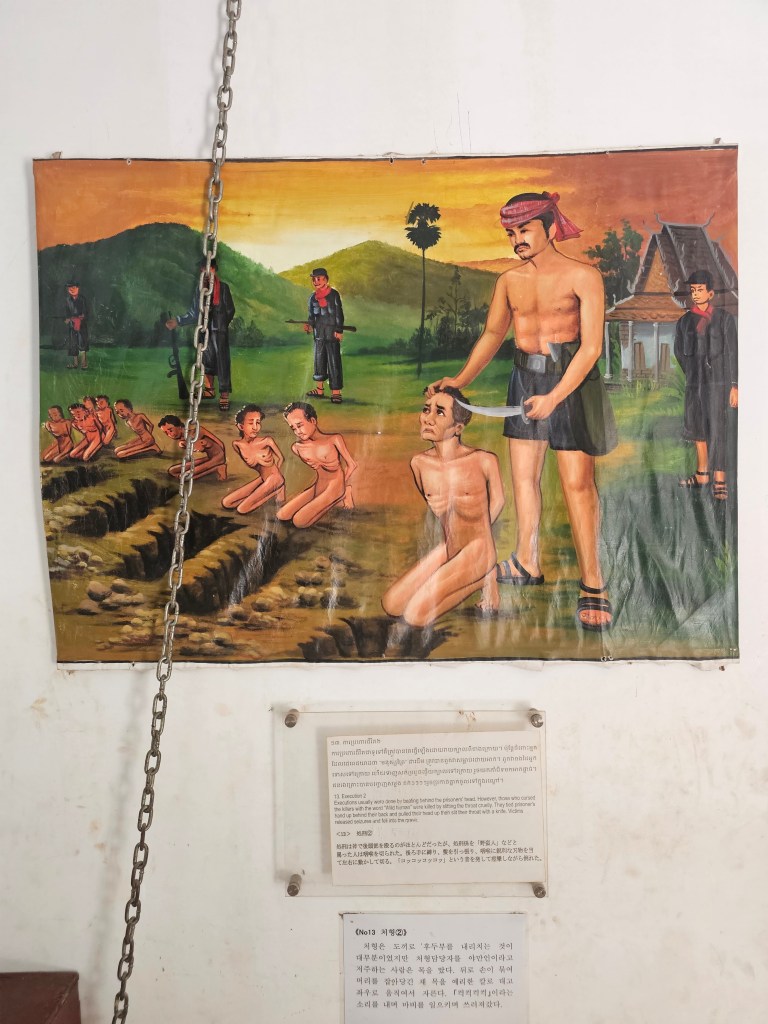

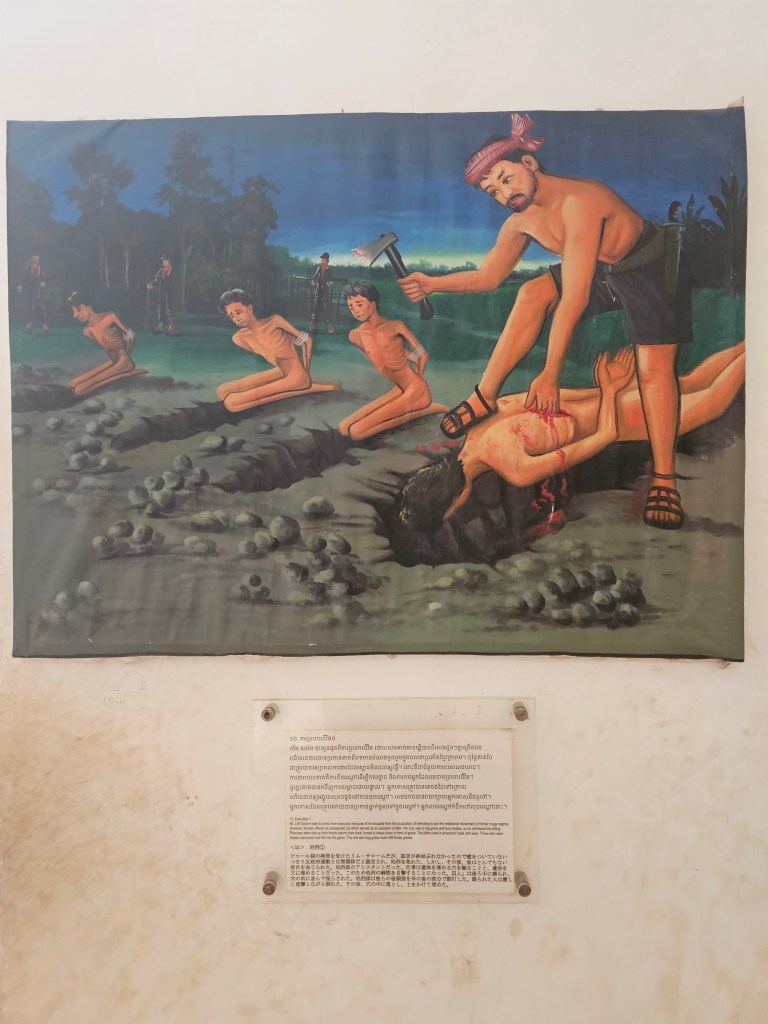

Paintings by one of the survivors of the Siem Reap Killing Fields, a former monk, Lim Sarorn. As with the Toul Sleng Prison, or S-21, not many would be so fortunate. These paintings chronicle the life and detention under the Khmer Rouge. Sum Rithy, another survivor, recounting life under the Khmer Rouge, and his time as a prisoner who survived the killing fields of Siem Reap.

Lim recounts that prisoners would dig mass graves before the prisoners arrived to the killing fields. The execution methods varied, but the use of the guns carried by the Khmer Rouge were not for execution, as they were not allowed to waste bullets when other methods were available. There is enough to view in a selection of the paintings that I will spare the gory details. Both of the main exhibits which are shared by both Lim and Sum Rithy, the second narrative are on display in the museum.

More paintings from the Siem Reap Killing Fields Museum, these scenes depicting several of the methods that the Khmer Rouge would execute the innocent. Included are images experience, Sum Rithy, another survivor, recounting life under the Khmer Rouge. He was only spared because he was knowledgeable about machinery and engines.

The second narrative of Sum Rithy, (distinguished by the wooden wall paneling), describes his life, being forced out of Siem Reap by the Khmer Rouge on April 17th, 1975. Much like Lim, Sum was forced to do hard labor in the countryside, share meals in a communal kitchen, and build a bridge. This continued into 1977 when one day he was rounded up by the Khmer Rouge and taken to Kuk Thom. While detained there he was told he was a secret CIA agent, and that he needed to confess. He repeatedly denied that he was with the CIA, that he only repaired motorbike engines. Eventually he was tested, told to repair some motorbike engines which he successfully did, which he suspected spared his life. Instead of being executed he was forced to continue repairing various engines until he was eventually released with the Vietnamese invasion on January 7th, 1979. Sum had also witnessed the ruthless methods of the Khmer Rouge, and his account of the execution of prisoners is also preserved by the Killing Fields museum.

Life in Cambodia during the Republic of Kampuchea, under Lon Nol, who lead the coup in 1970 that ended for a time the monarchy and gave the Khmer Rouge an important ally, the deposed prince, Sihanouk. The short lived republic would be ended on the 17th of April of 1975 by the Khmer Rouge.

After the Vietnamese freed the nation from the Khmer Rouge, survivors began to return. Some of these returning refugees would return to find their homes on the edges of the sites where the atrocities of the bloody regime were carried out. For a time, the local residents would find the grim evidence of the crimes of the Khmer Rouge in the form of bones and skulls of the victims in the very land beneath their feet. For a time, the remains were kept at the former detention center, left on the floor and slowly growing into an unmanageable pile. Between 1987 and 1990, the detention center was turned into a religious site, at first known as Wat Kbal Khmoch (Dead Skull Pagoda), more of a grave site than actual temple. This would change in the mid 1990’s when the prayer hall and other temple buildings started to make up the site, first called Wat Adthikaram, but later changed to the present name of Wat Tepothivong or Wat Thmey.

The well that the dead would be dropped into and a few of the mass graves that were left in situ at the Siem Reap Killing Fields Museum. Other remains near the pagoda were put into the memorial stupa.

With the temple taking shape, something needed to be done with the collection of artifacts that were kept on the grounds. More than 600 victims were originally found on the grounds of the site and from nearby, and more were yet to come. Eventually funds were raised to create a memorial stupa to build a proper pagoda to honor the victims. This first pagoda would be too small however, so an additional campaign to build a bigger stupa was made, giving the site the present memorial with over 800 skulls of the victims of the brutal Khmer Rouge regime. Across the nation, a collection of similar small pagoda style shrines have been erected, containing the remains of the victims of the Killing Fields. There are some 388 mass grave sites that have been identified across Cambodia from the Pol Pot regime, perhaps more yet to be discovered.

The stupa monument of the dead of the Siem Reap Killing Fields. Like the pagoda memorial at Choeung Ek, it houses the remains of the innocent victims.

Once the main course of the tour through the experiences of the death center are toured, arrows point visitors towards the macabre spectacle of the stupa in which is encased the skulls and bones of some 800 victims that were recovered from the Kuk Thom site. These bone stupas of the victims are controversial, as they already deviate from traditional burial practices, typically cremation. However, they also serve as a powerful tool that forces the visitor to become a spectator, to see the horrors we seem to be capable of inflicting unto our fellow man. It challenges our humanity, tolerances, and permissiveness that we continue to allow these atrocities to continue into the 21st century.

I know of three of these pagodas around Cambodia, found at the three largest detention and execution grounds I am aware of. I have already covered one at Choeung Ek, the other I am aware of is in Battambang, which will be covered at a later time. Visiting these sites is not a light hearted adventure, and for visitors fixated on the ancient ruins and part scene, visiting these pagodas can bring that light hearted party mood down. But I continue to advocate that such sites should not be ignored, especially if one wants the full Cambodia experience.

The macabre memorial shrine to the victims of the Killing Fields, I only know of three such shrines, though there are probably a few more.

I feel it is important for us to confront the dark past of the Khmer Rouge, and others, as it is probably the best way to overcome the dark past. It is hard for me to find appropriate ways articulate the horrors of the Khmer Rouge, so visiting these dark tourism sites gives me a means to convey my revulsion of the Pol Pot regime. Cambodia is still suffering from the scars of the Cold War and the Khmer Rouge, living with neighbors who may have been their tormentors during that time. This is something that has often baffled me, that all the cadres of the regime live free, no truth and reconciliation, no being held to account for their crimes. Perhaps this is the strength of the Khmer people, not in the horrors that the regime unleashed, but that the perpetrators have been reassimilated into the community. At least most of the Khmer Rouge leadership has now faced the tribunals and deserved prison time, far from perfect, but better than nothing.

The pagoda shrine dedicated to the victims of the murderous regime of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, the four sides confront you, you can’t look away, they are there in front of you, they were living suffering beings. These memorials are controversial but they make the most profound point, we can’t ignore them, they should never be forgotten.

I often feel that we have to do better, and the evils of the twentieth century must be confronted. The Khmer Rouge is but one example, how many atrocities do we pretend to ignore as they happen, and circle back years later and apologetically reminisce on our feeble understanding of past events. It is important then for us to genuinely look upon the history of such events as the atrocities under the Khmer Rouge, the Holocaust, the Holodomor, or the events in Palestine and confront them as they occur. The potential to change and make these crimes against humanity less likely to occur in the future is there if we seriously and honestly confront this evil. Sincere historical inquiry is crucial to our ability to learn from the past evils and atrocities, and to do better in the future. This confrontation against our inner evils is fundamental to our shared humanity and cultural identity and is our collective source of hope for a better future for humanity.

I believe that this is the former memorial pagoda enclosure that once housed the remains of the victims of the Killing Fields. The newer pagoda where the victims are currently housed is behind me as I took this photo. A statue of the Buddha is now occupying the space.

Unfortunately for the memorial, it doesn’t seem that it gets many visitors. During my lengthy stay at the memorial, reading every sign, every scrap of info, I observed only one other visitor who quickly overtook me, breezing through the exhibits. I understand that a memorial dedicated to the darker history of Cambodia is going to be overlooked by the majority of the visitors to Siem Reap in favor of the majestic temples of the ancient Khmer Empire. These same temples brought me to Cambodia. It is saddening that many visitors are likely unaware of the brutality of the Khmer Rouge, or have ever heard of Pol Pot. I know first hand as when I was a teacher in Korea, many of my co-workers had never heard of the Pol Pot regime. Cambodia was only known for its historic temples, several of them had even been to the ancient ruins, never having known of the Siem Reap memorial. Even now, my more youthful co-workers barely know of Cambodia, but are baffled that such personalities as Sihanouk and Pol Pot once ruled poor Cambodia.

I understand the challenge of interrupting a happy peaceful vacation to pay a visit to such a dark place. However, I feel that we do too much ignoring of the world in our day to day lives. Visiting a site of imponderable evil requires some fortitude, and its easy to dismiss the Asian Auschwitz in favor of something more sublime like Banteay Srei, but I implore visitors to challenge themselves and challenge this impulse to dismiss Kuk Thom. Leaving this site might build within us that courage to challenge our current day atrocities happening in Ukraine and Palestine. We are all human beings, and despite our differences, we still share a moral culture and historical ties, all of us. My apologies for my inadequate articulation of my thoughts on the matter.

A map of the Siem Reap Killing Fields Museum, 1. Ticket & Tourist Information, 2. Khmer Rouge Camp information, 3. Gallery giving an account of a former monk, Lim Sarorn, 4. A restored period enclosure, with photos documenting Cambodian History 1955-1979, 5. The well, where human remains were recovered, 6. An in situ mass grave, with bone fragments exposed to view, 7. Camp Kitchen and restrooms. (cut off is the memorial pagoda).

A haunting image of the skulls of the victims of the Killing Fields, the youth and younger individuals on the bottom, full grown adults on the middle two tiers, and the elderly on the top tier, as observed from the bones.

My time at Kuk Thom Siem Reap draws to an end, but I will be back. I make it a point to visit this site every time I am in Siem Reap. I am drawn to Wat Tepothivong, to the Killing Fields, to pay my respects to the victims and to make sure that the sites gets some traffic. Even if it is just myself or with an unfortunate friend who gets dragged along for a history lesson. We leave with a little less joy felt after the historic past grandeur of Angkor Wat, but a greater appreciation of life in the present.

At least the flowers still bloom.

In a visit that is likely punctuated with many to visit the ancient splendor of the Khmer Empire, it is important to remember the dark history that took place on the very ground that millions of visitors tread on. Many are often oblivious to the human misery that happened mere decades ago. It is of high importance to be reminded that Cambodia is more than a land of idyllic rice paddy and historic temples. And it is equally important that we don’t paint Cambodia solely as a dark tourism site. I hope that more attention is paid by visitors to the Killing Fields of Siem Reap memorial, and maybe challenge their own fears and stand against the tyranny of the world we so often ignore.

Leave a comment